The Self in Brain Research

This essay is divided into three sections. The first

one describes the process in which science progresses and why, based on the

rules of this model, there has been a shift from psychoanalysis to behaviorism

and from that school of thought to neuroscience. The second section compares

the treatments derived from these three perspectives in terms of effect size,

relapse, and long-term outcomes. The last division proposes a new paradigm

shift, grounded in the pros and cons of each field, towards

neuropsychoanalysis.

As mentioned before, the first focus of this paper

will be to describe the cycles, which elucidate how science develops throughout

time, proposed by the physicist and historian Thomas Kuhn. He made a notable

contribution in philosophy of science when he introduced the concept of

paradigm shifts in his book The Structure

of Scientific Revolutions. This notion could be summarized as a cycle that

science goes through composed of five steps: normal science, model drift, model

crisis, model revolution, and paradigm shift.

The first part of the cycle represents the agreed conditions

in which science operates and is able to conduct further research. Religion,

which was one of the first attempts at explaining natural phenomena, will be

used as an example to describe each of the five steps in Kuhn’s concept. An

example of how it was used as normal science would be that the existing

knowledge about the past and every future discovery in nature could be

explained with religious doctrine. Specifically, by using religion as a model

to interpret phenomena, illnesses and the recovery from them were attributed to

supernatural phenomena. This is seen in ancient Greek religion, which credited

Asclepius, the Greek God of medicine, with medical recoveries.

Additionally, discoveries could also be interpreted

within the same model. For example, Judeo-Christian scripture asserts that

humans were created in one day. However, after Charles Darwin developed the

concept of evolution, a large portion of the catholic church stated that the

first chapter of the Bible was meant to be taken metaphorically rather than

literally. As well as stating that evolution was true, but it was God that either

made it happen, facilitated it, or provided the correct ingredients for it to

occur.

The second step, the model drift, is when scientists

start encountering questions that the existing model cannot answer. It is

evident that there are questions that religion, as a model, cannot answer. For

example, the fact that a person’s health improved or deteriorated depending on

their diet suggested that diseases had a biological basis rather than a

supernatural one. In other words, the conflict can be seen in question that asks

whether illnesses have a biological cause or supernatural entities have an

effect in biology and that is why scientists and doctors see medical

improvements after a change in diet.

Nevertheless, the questions that it does solve are explained

within the parameters of the model. For example, people followed a series of religious

rituals, including prayer, in order to have a successful harvest. On one hand, when

this occurred, it was because the Greek Goddess Demeter was content with the

rituals. On the other hand, when there was not a successful harvest,

individuals would make the claim that Demeter was not satisfied. However, when

individuals realized that the success of crops depended on different factors

such as the land, weather, and fertilizer, rather than Demeter, they

categorized agriculture in the realm of natural phenomena, while other unknown

processes such as rain were still considered as part of religion. The notion in

this model that what cannot be explained by biology, physics, etc., is caused

by supernatural entities belongs to a concept known as God of the gaps. For

example, in the Bible, diseases have a supernatural cause, unless the

biological one is known. A specific instance of this would be that individuals

thought boils had a natural cause and to treat it, they used a “poultice of

figs”. On the other hand, the origin of leprosy was unknown, which meant that

its origin was attributed to God and people prayed to be healed.

Going back to the competing theories of whether

illnesses had a biological basis or it was a supernatural entity having an

effect on the physiology of an individual, it is important to note why in

science the former is favored over the latter. This preference comes from the

concept Occam’s razor, also known as the law of parsimony, developed by the

theologian and philosopher William of Ockham. He asserted that when a number of

competing theories are present, the simple one should be chosen over a complex one.

By returning to the previous example, it becomes evident that one theory

consists of one factor, which would be a biological abnormality, and the other one

depends of two, which would be a supernatural entity and the biological

abnormality. Based on Occam’s razor, the former should be favored for its

simplicity. Otherwise, scientists would be confronted with more conflicting

questions such as why supernatural entities have to intervene in biological

processes to create diseases rather than just causing them without intervention

or how a supernatural entity interacts with biology.

In addition, there is another reason why, according to

the law of parsimony, scientists use biology, rather than religion, as the

foundation for treating illnesses. As stated before, the two competing options

were either a physiological basis for disease or a supernatural being having an

effect on human biology. Either way, by only studying physiology, scientists do

not need to discard any theory since they both have biology as the cause of

disease, as well as evidence supporting them. In other words, by reducing

theories to a model that consists only of its most basic elements that have

evidence, scientists can continue to conduct research without the conflict that

arises of having two competing theories present.

However, when there are enough problems present that

the current model cannot answer, it is generally agreed that the model should

be dropped. This would be the third step: model crisis. Nevertheless, a model

is abandoned only when there is another one that can solve the problems its

predecessor could not. For example, Newton proposed laws of motion and

gravitation that had evidence supporting them. Nevertheless, physicists could

not determine the motion of the moon based on Newton’s law. In order to obtain

it, some scientists tried to change it by substituting the inverse square law with

one that diverged from it at shorter distances. Since there were not enough

puzzles unsolvable by this model, it remained unchanged until 1750, when there

was a paradigm shift.

The fourth step would be a model revolution. This is

when a new model is created, one that is incompatible with the old one, but it

is better at answering questions the old model could not. By retaining the

example of religion, it would be evident that this could be exemplified by the four-temperament

theory that was incorporated into medicine by the philosopher Hippocrates. This

consisted of four bodily fluids: black bile, yellow bile, sanguine, and phlegm.

When they were balanced, an individual would be healthy, but when there was any

lack of stability of any of the fluids, a series of different ailments would arise.

The new model of temperaments is better than the previous one for two main

reasons. The first one is that it was able to answer some of the questions

religions could not. For example, when a person got better after getting

treatment with a variety of herbs and foods, but one who did not get treatment

did not get better, religion was not able to solely claim God as the reason why

people got better. Instead, they had to accept a biological component. Thus,

doctors started to treat diseases as a physical problem rather than a

supernatural one. The second reason is that treatments started to be

individualized. Each disease was given a specific treatment and this was more

helpful than treating them all equally. Finally, a paradigm shift, which is the

last step, consists of adopting the new model. This would mean that, once again,

scientists go back to the first step turning this new model into normal

science.

The fourth step would be a model revolution. This is

when a new model is created, one that is incompatible with the old one, but it

is better at answering questions the old model could not. By retaining the

example of religion, it would be evident that this could be exemplified by the four-temperament

theory that was incorporated into medicine by the philosopher Hippocrates. This

consisted of four bodily fluids: black bile, yellow bile, sanguine, and phlegm.

When they were balanced, an individual would be healthy, but when there was any

lack of stability of any of the fluids, a series of different ailments would arise.

The new model of temperaments is better than the previous one for two main

reasons. The first one is that it was able to answer some of the questions

religions could not. For example, when a person got better after getting

treatment with a variety of herbs and foods, but one who did not get treatment

did not get better, religion was not able to solely claim God as the reason why

people got better. Instead, they had to accept a biological component. Thus,

doctors started to treat diseases as a physical problem rather than a

supernatural one. The second reason is that treatments started to be

individualized. Each disease was given a specific treatment and this was more

helpful than treating them all equally. Finally, a paradigm shift, which is the

last step, consists of adopting the new model. This would mean that, once again,

scientists go back to the first step turning this new model into normal

science.

In psychology, there have been different models that

attempt to explain behavior and mental processes such as psychoanalysis, behaviorism,

and neuroscience. The first model, which was founded by Sigmund Freud, consists

of a paradigm that revolved around the mind. Freud, who was a neurologist,

divided the mind into three parts in two different instances. The first time,

he stated that the three divisions were the conscious, the preconscious, and

the unconscious. The former contains everything an individual is aware of. For

instance, when a person thinks of what they are going to wear for the day. The

preconscious contains notions that a person is not aware of but can bring to

the conscious if they choose to such as a person who is not consciously

thinking of what they wore the day before, but they can remember if they intend

to. Lastly, the unconscious contains material individuals are not aware of

because it is being repressed. The second time he divided the mind was into the

ego, the superego, and the id. To summarize them with the risk of

oversimplifying them, the ego regulates the social and moral demands from the

superego in order to satisfy the wishes and drive from the id.

In terms of normal science, phenomena would be

explained as a result of the different dynamics between this tripartite model.

For example, Freud theorized that dreams were the disguised fulfillment of

suppressed wishes demanded by the id. He asserted that children’s dreams were

easier to elucidate because their dreams were not censored. However, after an

individual reached a certain age, he or she would develop their superego, which

reminds the ego, that there are wishes that should not be fulfilled because of personal,

moral, social, political, and/or religious values and rules. The ego then

decides how the content should be distorted. If a wish does not break any of

the superego rules, then, there is minimal censorship such as a man who was

thirsty during the evening and dreams that he drinks water.

There are other phenomena that can be explained by

psychoanalysis in terms of the dynamics between the ego, superego, and id such

as jokes, parapraxes, religion, sexuality, development, emotions, etc. This

would constitute descriptive science. However, psychoanalysis can also be

applied as a form of therapy.

To examine its effectiveness in normal science,

psychoanalysis as a provider of treatment will be examined using its effect

size. This quantifies the difference between the experimental and control group

in standard deviation units. Specifically, an effect size of 0.2 would be

considered small, an effect size of 0.5 would be considered to have a moderate

effect, and a 0.8 would be considered a large effect size (Cohen, 1988). It is

important to first describe the effect size of psychotherapy in general. The

first major meta-analysis, which looked at 475 studies that compared people who

received therapy to those who did not, found an effect size of 0.85 (Smith,

Glass, & Miller, 1980), while a later study found an effect size of 0.75

(Lipsey and Wilson, 1993). This provides evidence that psychotherapy has a

large effect size and it is effective in treating mental illnesses.

In terms of psychoanalysis, the Cochrane Library

conducted a meta-analysis of 23 randomized trials with 1,431 patients (Abbass,

Hancock, Henderson, & Kisely, 2006). The meta-analysis looked at four types

of categories of symptoms, which were general symptoms, somatic symptoms,

anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms, of people who attended therapy for

forty hours and were compared to either a wait list, treatment as usual, or

minimal treatment. In addition, there were three different types of follow-up

periods. A short-term one, which was under three months, a medium-term, which

was between three and nine months, and a long-term, which consisted of anything

longer than nine months. For general symptoms, there was an effect size of 0.97

with an effect size of 1.51 after a long-term follow-up. For somatic symptoms,

it was 0.81 with a long-term follow up of 2.21 and anxiety had an effect size

of 1.08 with a follow up of 1.35. Finally, depressive symptoms had an effect

size 0.59 with a follow up of 0.98. This demonstrates that psychoanalysis

effectively plays the role as a descriptive and applied form of science in the

first step of Kuhn’s cycle.

However, it is not effective with every mental

illness. This qualifies it to be a model drift. For example, a study that

included four randomized trials and 528 patients compared psychoanalysis or

psychodynamic therapy, medication, and other types of therapy in their

treatment of schizophrenia (Malmberg, Fenton, &Rathbone, 2001). Malmberg

found that patients in psychodynamic therapy tended to remain unqualified to be

discharged compared to a group that only received medication. Moreover, he did

not find a difference between therapy and medication compared to medication

alone in terms of suicide or ability to be discharged. The authors also found

that it was unclear whether there was a difference in the number of patients

who were re-hospitalized after receiving long-term psychoanalytic therapy. In addition,

there was no difference between psychodynamic therapy and reality adaptive

psychotherapy in terms of re-hospitalization. However, patients tended to end

psychodynamic therapy before there was a clinically significant response compared

to the reality adaptive therapy. Finally, at a follow up of 12 months and one

of 3 years, it was found that less patients undergoing psychoanalytic therapy

needed extra medication compared to the group that received medication alone.

The authors’ conclusion was that since there was a small amount of studies that

studied therapy without medication, the results were still inconclusive.

Nevertheless, it is evident that medication is an important component that aids

people with schizophrenia and it should be combined with therapy (Malmberg,

Fenton, &Rathbone, 2001).

This, as it was stated before, is the second step in

Kuhn’s cycles of science. However, this is not enough to cause a paradigm

shift. What produces the model crisis was a focus on evidence-based empiricism

only. The reason for this shift was because there was evidence for different theories

based on models that conflicted with each other. One of them is psychoanalysis,

which had the mind as a foundation, and behaviorism, which was grounded around behavior.

An example of how the conflict is present can be seen in a research paper

written by John B. Watson, who was the founder of behaviorism. He affirms that

the concept proposed by Freud of transference, which Watson defines as

patients’ love reactions, is true. However, instead of this being a result of

the dynamics of the mind, which is the paradigm of psychoanalysis, it was an

outcome of habit formation, which is a concept derived from behaviorism (Watson, J. B., &

Morgan, J. J., 1917). Scientists at that time had to make a choice

between both of them and the decision made was taken for two reasons. The first

one, as it was mentioned before, was the focus on evidence-based empiricism. Since

there has not been empirical evidence of the mind, the idea was rejected. It is important to introduce the concept of monism

and dualism. The former asserts that individuals interpret reality with

something that is made up of one material, which could be either a psychical

apparatus like the mind or something made up of matter such as a brain. Dualism

asserts that the mind interacts with the body. Since there is no empirical

evidence for the mind, one type of monism is rejected. The other two possible alternatives

are a matter-based monism or dualism. However, by referring back to Occam’s

razor, dualism has to be rejected over monism since it is a more complex

theory. For these reasons, the model of behaviorism was accepted. Thus, forming

part of the last two steps of Kuhn’s cycle.

Nevertheless, it is important to mention that the

simplest theory is not always the correct one. After another paradigm shift, it

was agreed by the scientific community that behaviorism by itself was an

inadequate model. By trying to reduce everything to behavior, it ignored the

biological component to human nature. This was solved by combining both nature

and nurture. Thus, integrating neuroscience with behaviorism. As a form of

treatment, this resulted in psychopharmacology and cognitive behavioral therapy

(CBT). The effectiveness of both will now be presented to determine their

validity in replacing psychoanalysis and their role in normal science.

Before

examining the effectiveness of medication, it is important to describe how it

works in the brain. The brain is an organ made up of cells known as neurons, which

communicate using chemical signals that involve neurotransmitters such as

serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. The turnover model, which is composed

of five steps, explains the process neurotransmitters undergo in order for them

to be released and have an effect. It is important to note that drugs

specifically target one or more of these steps in order to be effective. The

first step is biosynthesis, which is when the presynaptic cell synthesizes

neurotransmitters when a precursor interacts with an enzyme. For example, when

the precursor tyrosine interacts with the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, it

becomes L-Dopa, and when that precursor interacts with the enzyme DOPA

decarboxylase, the outcome is dopamine. Then, the second step is storage. This

is when the neurotransmitters are stored in vesicles, which fuse to the

membrane so they can be released. This release is the third step and it is

called exocytosis. Exo- meaning outside, cyto- meaning cell and -sis referring

to a process. In other words, the process in which a neurotransmitter is released

outside of the cell. Neurotransmitters travel into the space between the

presynaptic and postsynaptic cells, known as the synaptic cleft, where they

bind to the receptors located in the postsynaptic cells. After they bind, the

neurotransmitters have three options. The first one is that they can travel to

the extracellular space, thus, becoming lost. The second option is the fourth

step of enzymatic degradation. This refers to the fact that they can also be

broken apart by enzymes, such as monoamine oxidase (MAO). The final option and the

fifth step is reuptake, which describes how a neurotransmitter can be recycled

by a protein known as a transporter that picks it up and returns it to the

presynaptic cell where it can be reused later on. Another concept that is

important to explain would be of agonists and antagonists. The former simulates

a neurotransmitter by binding to the postsynaptic receptor and activating it.

The latter also binds to the postsynaptic receptors, but it blocks them, not

allowing the neurotransmitters to bind and activate them.

The most common type of an antidepressant is a

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). This means that the drug blocks

the transporter that recycles serotonin. Therefore, this neurotransmitter

spends more time in the synaptic cleft. Thus, increasing the chances of binding

to the postsynaptic receptors. This suggests that depression is correlated with

not enough post-synaptic receptor activation by serotonin. Therefore,

neuroscience is effective at conducting normal science by describing phenomena

according to its model. However, it is now critical to examine its validity at being

an applied science.

To inspect the efficacy of antidepressants and CBT, the

STAR*D study will be examined. It became the largest study of depression

treatment to date by examining more than 4,000 patients in 41 different centers

across the United States (Gaynes et a., 2008). It consisted of four treatment levels.

In the first one, patients received the SSRI Citalopram for a period of 12 to

14 weeks. If the patients responded well to the medication, there would be a

follow-up period of 12 months where the patients were still under their

medication. If the Citalopram did not have an effect on the patient or if the

patient had severe side effects, they would continue to the second level, which

consisted of three major options. One of the major possibilities had three

subdivisions. The first one was either using another SSRI such as Sertraline

instead of Citalopram. The second option was using an antidepressant that

targeted a different neurotransmitter’s system such as Bupropion, which is a

norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI). The last possibility was

taking an antidepressant that worked within the serotonin and another neurotransmitter’s

system such as Venlafaxine, which is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake

inhibitor (SNRI). The second major option was either adding an NDRI

antidepressant to an SSRI such as Bupropion with Citalopram or an SSRI with

medication that would enhance it such as Buspirone, which is a serotonin

agonist. The third option was CBT by itself or paired with an SSRI. If after

there was no effect or if there were harsh side effects, patients were moved to

the third level.

This

new level consisted of either adding a new medication that had evidence of

aiding SSRIs such as Lithium, which helps synthesize serotonin or switching

medication that had a different mechanism of action such as Mirtazapine, which,

counterintuitively, works as a serotonin antagonist. As done in the levels

before this one, if patients did not get better or if their symptoms were

intolerable, they were moved to the fourth level. In this level, patients

received a new type of medication such as tranylcypromine, which is an MAOI, or

a combination of Venlafaxine and Mirtazapine. By covering every step in the

turnover model, scientists could find which system in the brain is responsible

for depression and how to target it.

It

took six weeks on average to see a response to the antidepressants and almost

seven weeks for individuals to obtain remission. Additionally, on average,

patients visited their doctor between five to six times. The remission rates

were on average of 67%. The rates per level were 33% for the first level, 24%

for the second one, 6% for the third, and 4% for the last level (Gaynes et al.,

2008). In addition, those who went through more levels had higher relapse rates

and were more likely, both patient and doctor, to settle for a response. After

follow-up, those that had achieved remission instead of response had a better

prognosis at the 12-month follow-up. Moreover, the relapse rates after the 12-month

follow-up period were 40.1% in the first step, 55.3% in the second, 64.6% in

the third, and 71% in the fourth step. The average months it took for

patients to relapse were 3.6 across all levels, 4.1 in the first level,

3.9 in the second one, 3.1 in the third, and 3.3 in the last level (Rush et

al., 2006). This means that, on average, by the second level more than half of

the participants were going to relapse on their depression within three months

of the follow-up period. In addition, it

is important to consider the size effect of medication. An FDA study found an

effect size of 0.26 for fluoxetine and sertraline, 0.24 for citalopram, 0.31

for escitalopram, and 0.30 for duloxetine. Moreover, a meta-analysis found an

effect of 0.17 for tricyclic anti-depressants (Moncrieff, Wessely, & Hardy,

2004) when compared to an active placebo.

It is crucial to describe

the negative characteristic of medication, which include its side effects. The

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did a review in 2004 of clinical trials of patients

that took antidepressants, including, but not limited to, SSRIs. The conclusion

of the review was that there was an increase of risk of suicidal thinking and

behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults that were under

antidepressants

(Suicidality and Antidepressant Drugs - FDA., n.d.). Specifically, a

jump to four percent compared to two percent from the control group (“Antidepressant

Medications for Children and Adolescents,” n.d.). As a result of

antidepressants doubling the risk of suicidal behavior, the FDA put a black box

warning the following year in order to alert consumers. It is important to note

that there were no suicides committed in the study. In addition, another common

side effect is the worsening of depression. Therapy is usually paired with

medication to reduce these side effects.

In addition, the same

medication used as an antidepressant is given to people who have either a mood

or an anxiety disorder. According to the anxiety and depression association of

America (ADAA), anxiety and mood disorders are the most common mental illnesses

in the U.S. since they affect more than forty million Americans, totaling

around 18% of the population every year (“Facts & Statistics,” n.d.). The

side effects of the most common medication for PTSD include

convulsions, sudden loss of consciousness, loss of bladder control, muscle

spasms, blurred vision, dry skin, chest pain, weight gain or loss, hair loss,

heartburn, indigestion, and insomnia between others (“Sertraline Side Effects in Detail,” n.d.). This means that the majority of people who need

mental health treatment receive the same type of medication and may experience

the some of the same side effects.

The other form of treatment is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. The remission and

relapse rates were already provided in the STAR*D study. The effect size of CBT

depends on what it is treating. Therefore, a meta-analysis that examined its

effectiveness on different disorders will be used. In the treatment of cannabis

dependence, CBT had efficacy. However, it was a small effect size compared to

other psychosocial treatments such as relapse prevention and medication showed a

greater size effect in treating other dependencies with other drugs such as

alcohol and opioids (Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T.,

& Fang, A., 2014). In addition, CBT can reduce the positive symptoms of

schizophrenia and it is helpful when paired with antipsychotics in order to

treat acute episodes of psychosis. However, the effects disappear with patients

that live with a chronic disorder (Hofmann et al., 2014). It had little effect

on relapse and medium effect size for improvements in secondary outcomes such

as social anxiety.

Compared

to a wait list, in terms of major depressive disorder, CBT had an effect size

of 0.82 and compared to medication, it was 0.38 (Butler, A., Chapman, J.,

Forman, E., & Beck, A. 2006). However, CBT was as effective when compared

to other therapies such as psychodynamic therapy (Hofmann et al., 2014). In

addition, there is little evidence that CBT is effective in treating the

symptoms of bipolar disorder and the effects of it disappear at follow-up. With

general anxiety disorder (GAD), it has an effect size of .82 when compared to a

waitlist (Butler et al., 2006). In terms of personality disorders, a comparison

between CBT and psychodynamic therapy showed that the latter had a larger

effect size (Hofmann et al., 2014). For mood disorders, CBT was as effective as

psychodynamic therapy and interpersonal therapy.

Up until now, it seems that CBT and psychoanalysis are

equally effective in treating some disorders such as depression (Leichsenring, F., 2001). In addition, both tend to be

superior to medication. However, it is important to note that there is a

publication bias in favor of CBT and that its effect sizes are overestimated,

especially in lower quality research papers (Cuijpers et al., 2013).

Moreover, there is also a publication bias in favor of medication (Turner, E., Matthews, A., Linardatos, E., Tell, R.,

& Rosenthal, R., 2008). Moreover, a meta-analysis did not find a

publication bias in favor of psychoanalysis (Leichsenring, F., 2008). The bias for medication

is shown in a meta-analysis that examined 78 studies with 12, 564 patients and

12 antidepressant agents. Turner, along with other contributors of the

article, found that out of those 78 studies, 38 were positive and all of them

except one were published (Turner et al., 2008). Out of the thirty-six studies

left, 24 were and negative and 12 were questionable. From these, three were

published as unsuccessful, 22 were not published, and 11, while contradicting

the outcome of the FDA, were published as positive (Turner, 2008). The 51% of

positive studies had an average effect size of .37 for published studies and a

.15 for unpublished studies (Turner, 2008). The negative results are usually

left unpublished, and the positive ones, which have a tendency to be published,

only show a small effect size. This means that antidepressants are not as

efficient in achieving their purpose compared to other forms of therapy and

that there is a bias when it comes to publishing evidence on

psychopharmacology’s effects.

CBT

does not have side effects, but it does have limitations. One of them is its

lasting effects on patients. One study that examined the effectiveness of CBT

in anxiety disorders, which is the category where CBT is the most efficacious,

and psychosis found that the short-term outcomes disappear over long periods of

time. In addition, it did not matter whether the therapy was conducted in the

usual ten sessions or if it was a more intensive version. Moreover, CBT was not

more cost-effective when compared to other forms of therapy (Walley, 2006).

By

summarizing the data above, it becomes clear that psychoanalysis is a great

form of treatment. It is more effective than medication and CBT in some

disorders and equally as effective as CBT in others. However, the effect size

of CBT and medication are overestimated since there is a publication bias in

favor of them. This becomes alarming when it is shown that only half of the

studies done on antidepressants are positive. Moreover, psychoanalysis does not

share the same side effects of medication or the relapse rates of CBT and drug

treatments. In fact, after long-term follow ups it seems that patients that

underwent psychoanalytic therapy keep improving. For example, a study found

that psychoanalytic therapy had an effect size of 0.78 for mixed and moderate pathology

and an effect size of 0.94 at a follow up of 3.2 years, for reducing symptoms

it was 1.03, and 0.54 for personality change. For severe pathology, the effect

size was 0.94, 1.02 at a follow up of 5.2 years, and 1.11 in personality change

(Maat, S. D.,

Jonghe, F. D., Schoevers, R., & Dekker, J., 2009). For

psychoanalysis, there was an effect size 0.87, with a follow up of 1.18, a

symptom reduction of 1.38, and an effect size of .076 for personality change.

Thus

far only short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy has been examined. Therefore, evidence

for long-term will be examined. A meta-analysis that looked at eight studies

found that when compared with other types of therapy, long-term psychodynamic

therapy had an effect size of 0.96 compared to 0.47 in overall effectiveness, 1.16

compared to 0.61 in target problems, and 0.90 compared to 0.19 in personality

functioning (Leichsenring,

F., 2008).

The next important point is to explain the reasons why

psychoanalysis is so effective. One of the reasons might be that it is an

individualized form of treatment. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a scripted

treatment and the same dose of the same drug is given to relatively all

patients at the start of their treatment. Doses and the drug are later changed,

depending on how a person reacts to it. In addition, studies show that medication

does not work equally with different subgroups of people. One of them being

children and, as was mentioned before, side effects affect this population

differently. However, psychoanalysis is individualized from the start. As Carl

Jung, an important psychiatrist in the field of psychoanalysis, stated in his

book The Undiscovered Self: “For the

more a theory lays claim to universal validity, the less capable it is of doing

justice to the individual facts.” As mentioned before, one of the advantages

made from changing paradigms from religion to the four-temperament theory was

that the there was a change from equal treatment, which was prayer, etc., to a

treatment specific to each disease.

Another crucial

aspect is that it involves subjectivity. This goes against the objectivity

mindset of science. Therefore, the question arises of why it should be an

important part of the field. The answer is that the subjectivity avoided in

science belongs to the personal point of view of a scientist investigating an

object (i.e. a chemical, a cell, actual matter). However, humans are both an

object and a subject. It is true that individuals, objectively, share certain

experiences. Nevertheless, they also do it subjectively and this is overlooked

in neuroscience and CBT, which seems counterintuitive since it forms an

important component of the human experience. For example, neuroscientist and

psychoanalyst Mark Solms gives a description of why subjectivity can be an

important component. He describes five patients in his book The Feeling Brain: Selected Papers on

Neuropsychoanalysis.

The first one was Mrs. A, who was a retired nurse that

had suffered a ruptured aneurysm in the right middle cerebral artery of her

brain. Her symptoms included neglecting the left side of her body, recognizing

it belonged to her, and spatial disorientation, which are typical of her

injury. However, she was referred to a therapist for her depression, which is an

unusual symptom for her condition. In fact, it was affecting her so much that

she had attempted suicide twice. She reported that the cause of her depression

was because she kept losing everyday objects and because everybody hated her.

After further explanation, Mrs. A stated that these two causes were an outcome derived

from her loss of independence. The ironic thing is that she was indirectly

aware of her condition since she was conscious that people around her had to

take care of her, but she was not aware why. This notion of loss was

transferred to other familiar losses and she asserted that they also caused her

depression. These included the loss of her father, a hysterectomy, and everyday

objects.

After analysis, it was shown that she had denied the

loss by means of introjection. This was a concept developed by Freud in his

paper “Mourning and Melancholia.” In here, he asserted that when an object that

an individual ambivalent loved and was narcissistically invested in was lost,

the loss would be repressed by means of unconscious introjection. Since the

object was also hated, the individual has to despise himself or herself. This

occurs because the existence of the object undergoes introjection and no longer

conscious. This is what occurred to Mrs. A. Therefore, her idea that everyone

hated her was an internal projection that came from her hating her left side of

her body for losing her independence.

Two more patients, which Solms referred to as Mrs. B

and Mr. C, had experienced strokes on the right side of the brain. Since both

of them had the same physiological damages in the same part of the brain, they all

ended up sharing the same symptoms as Mrs. A. These ranged from the ignoring of

the left side of their bodies to the spatial disorientation with the exception

of Mrs. A’s depression. Instead, their symptoms included a shade of narcissism.

Their sense of superiority was paradoxical since they were demanding, but

unaware of the condition that made them dependent. Unconsciously, they were deeply affected by

the unilateral neglect. This is evident since after sessions “they understood a

sense of loss, humiliation, and failures.” As Freud asserted, a possible

defense is when there is an introjection of the libido of the object back into

the ego. So far it has become evident that the three patients have dealt with their

injuries by undergoing introjection part of themselves back into the ego, which

created the neglect of the injury.

The last two patients who suffered the same

physiological damage, Mr. D and Mr. E, were narcissistic in a different sense.

They were “impatient, imperious, obsessive, hyperactive, intolerant and

frustrated.” They made demands to the doctors to either cure their left side of

their body or amputate it. If it did not happen, they would either do it

themselves, kill the doctors, or kill themselves. They neglected the injury,

which had placed them in the hospital in the first place and blamed the doctors

for their condition. In this case, there was no introjection, but rather a

projection of the lost object and a hate towards it. In conclusion, the first

three patients internalized the lost object into their ego, where it was

attacked. This is evident in the notion that Mrs. A had depression and had

attempted suicide twice and Mrs. B and Mr. C on the crying in session consumed

over past losses. The last two patients projected the cause of the loss of the

object to the outside by claiming it was the doctors’ fault that they had the

alien limbs attached to them and it was their responsibility to amputate them.

In addition, the hate projected is seen in the threats made by the patients to

doctors and themselves.

The

important thing here is that all of the patients had suffered the same

physiological lesion in the same area of the brain. However, they handled their

injury in different ways. The loss of control over the left side of their body

was experienced as a narcissistic wound that was accompanied with a feeling of

loss and dependency of the object lost. There were two possible solutions as a

defense for this injury, which were either an introjection of the cathected

lost object or a projection. What these cases

suggest is that damage in the right hemisphere produces failure of the process

of mourning.

The

important point to note here is that they all had the same brain injury. If the

brain of the five patients had been examined with different tools there would

not be a difference that showed that the patients were processing their

injuries differently. It was only when subjectivity was involved that these

differences were noticed and treated, which could suggest why psychoanalysis is

better in treating some disorders than other treatments. This means that there

are two perspectives when treating and understanding a person. One of them is a

physical, which refers to neuroscience. As mentioned before, this field has an

advantage over psychoanalysis over some criteria such as the treatment of

schizophrenia or the ability to look at biological data. The other point of

view is psychical, which refers to psychoanalysis. As mentioned before, this

field has an advantage over neuroscience over some criteria such as the

treatment of depression and the ability to look at subjective data.

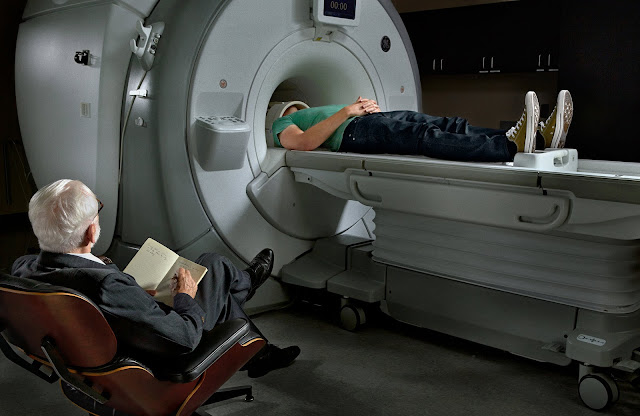

This

is why a new paradigm is in order. One that advocates for neuropsychoanalysis.

As it has been explained before, neuroscience has been conducting normal

science. For example, in terms of addiction, neuroscience asserts that in the

mesolimbic pathway there is a structure called the nucleus accumbens, which is

associated with the seeking of pleasure. From the same starting point of that

pathway, begins a different one called mesocortical pathway, which includes a

structure known as the prefrontal cortex that is in charge of inhibition,

planning, and regulating behavior. This is compatible with the Freudian model

of the mind. In fact, the nucleus accumbens shares the same functions as the id

and the superego shares similar functions with the prefrontal cortex. Moreover,

these brain areas are activated while a person dreams much as it would be

expected from the id and superego. In fact, damage to the ventromedial

prefrontal cortex is the only damage that can cause cessation of dreaming.

There is a model drift in neuroscience, which is that the treatments derived

from it are not as effective. A model crisis could be when it is seen that

neuroscience cannot account for subjectivity. As mentioned before, it can find

and explain the right hemisphere trauma, but it cannot predict or even look at

how individuals respond to this trauma. A model revolution would be the

proposal of a new paradigm shift, which in this case would be

neuropsychoanalysis. The same way there are tools used to find and treat

neurological injuries, the use of psychoanalytic techniques would be employed

to treat these psychological symptoms. For example, a CT scan would find the damage

in the right hemisphere of the brain and neuroscience would be able to explain

what caused the hemiplegia. However, the different symptoms of depression,

indifference, and obsession were only found by applying psychoanalytic therapy

and explained by introjection, denial, and projection, which are psychoanalytic

concepts.

Nevertheless, psychoanalysis does not only need to be

clinically effective to be used in a paradigm. This is clearly seen in the

early paradigms of hypnosis, where Mesmer, who was a key factor in the

foundation of hypnosis, explained it in terms of animal magnetism. Even though,

hypnosis worked, the theoretical background behind it is now rejected.

Therefore, the possibility arises of what if psychoanalysis is clinically

effective, but not theoretically right. Especially taking into the

considerations of how scientists have arrived at the existing paradigm. Thus,

it is important to justify psychoanalysis from an epistemological point of view.

If

the previous paradigm shift was made on the basis that there is no empirical

evidence of the existence of the mind, there is no reason why scientists should

go back and accept it into their existing model of science. The answer to this

is a dual aspect-monism. This claims that individuals are only made up of one

material, but this can be perceived in two ways, objectively with the help of

neuroscience and subjectively with the help of psychoanalysis. In addition, one

of the reasons why there was a paradigm shift from behaviorism to neuroscience

is because Occam’s razor was rejected and it was understood that individuals

were more complex. The existing model of neuroscience and behavior are also not

complex enough since they do not take into account the subjective human

experience.

In

conclusion, science changes in cycles based on epistemological reasons. This explains

the paradigm shifts from psychoanalysis to behaviorism to neuroscience.

However, by taking different criteria into account, it becomes evident that

psychoanalysis is a superior form of treatment when compared to medication and

CBT in some disorders and equal to others. The fact that it is an individualized

form of treatment and that it incorporates individuals’ subjectivity into the

model might be some of the reasons why psychoanalysis is so effective. Therefore,

a new paradigm on a neuropsychoanalytic model is justified on epistemological

grounds by championing dual-aspect monism and the advantages of psychoanalysis

and neuroscience.

References

Abbass, A. A., Hancock,

J. T., Henderson, J., & Kisely, S. (2006). Short-term psychodynamic

psychotherapies for common mental disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews, Issue 4, Article No. CD004687. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004687.pub3

Antidepressant

Medications for Children and Adolescents: Information

for Parents and Caregivers. (n.d.). Retrieved from

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/child-and-adolescent-mental-health/antidepressant-medications-for-children-and-adolescents-information-for-parents-and-caregivers.shtml

Butler, A., Chapman, J.,

Forman, E., & Beck, A. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral

therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review,26(1),

17-31. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003

Cohen, J. (1988).

Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Cuijpers, P., Berking,

M., Andersson, G., Quigley, L., Kleiboer, A., & Dobson, K. S. (2013). A

Meta-Analysis of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Adult Depression, Alone and

in Comparison with other Treatments. The Canadian Journal of

Psychiatry,58(7), 376-385. doi:10.1177/070674371305800702

Facts & Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://adaa.org/about-adaa/press-room/facts-statistics

Gaynes, B., Rush, A.,

Trivedi, M., Wisniewski, S., Spencer, D., & Fava, M. (2008). The STAR*D

study: Treating depression in the real world. Cleveland Clinic journal of

medicine. 75. 57-66. 10.3949/ccjm.75.1.57.

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani,

A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2014). Erratum to: The Efficacy

of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses. Cognitive

Therapy and Research,38(3), 368-368. doi:10.1007/s10608-013-9595-3

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of

scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago

Press.

Leichsenring, F. (2001). Comparative effects of

short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in

depression. Clinical Psychology Review,21(3), 401-419.

doi:10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00057-4

Leichsenring, F. (2008). Effectiveness of Long-term

Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. Jama, 300(13), 1551.

doi:10.1001/jama.300.13.1551

Maat, S. D., Jonghe, F. D., Schoevers, R., &

Dekker, J. (2009). The Effectiveness of Long-Term Psychoanalytic Therapy: A

Systematic Review of Empirical Studies. Harvard Review of Psychiatry,17(1),

1-23. doi:10.1080/10673220902742476

Malmberg L, Fenton M, Rathbone

J. Individual psychodynamic psychotherapy and psychoanalysis for

schizophrenia and severe mental illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews 2001, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001360. DOI:

10.1002/14651858.CD001360.

Moncrieff, J., Wessely, S., & Hardy, R. (2004).

Active placebos versus antidepressants for depression. Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews, Issue 1, Article No. CD003012. doi:10.1002/14651858.

CD003012.pub2

Rush,

A., Trivedi, M., Wisniewski, S., Nierenberg, A., Stewart, J., Warden, D., Niederehe, G., Thase, M., Lavori, P., Lebowitz, B., McGrath, P., Rosenbaum, J., Sackeim, H., Kupfer, D., Luther, J., Fava M. (2006).

Acute and Longer-Term Outcomes in Depressed Outpatients Requiring One or

Several Treatment Steps: A STAR*D Report. American Journal of

Psychiatry,163(11), 1905. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.11.1905

Sertraline Side Effects in Detail.

(n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.drugs.com/sfx/sertraline-side-effects.html

Smith, M. L., Glass, G. V., & Miller, T. I. (1980).

The benefits of psychotherapy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Suicidality and Antidepressant Drugs - FDA. (n.d.).

Retrieved from

https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM173233.pdf

Turner, E., Matthews, A., Linardatos, E., Tell, R.,

& Rosenthal, R. (2008). Selective Publication of Antidepressant Trials and

Its Influence on Apparent Efficacy. 284-285. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa065779

Watson, J. B., & Morgan, J. J. (1917). Emotional

Reactions and Psychological Experimentation. The American Journal of

Psychology,100(3/4), 510. doi:10.2307/1422692

Walley, P. T. (2006). Long-term outcome of cognitive

behaviour therapy clinical trials in central Scotland. Clinical

Governance: An International Journal,11(2).

doi:10.1108/cgij.2006.24811baf.003

Comments

Post a Comment