The Five Lectures of Freud: An Introduction to Psychoanalysis

Sigmund Freud, a neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, made his first and only trip to the United States in 1909 (Jay, 2016). Stanley Hall, who was the first person to receive a PhD degree in psychology in the U.S., and the first president of the American Psychological Association, had invited Freud to Clark University to lecture on psychoanalysis (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2016c). The lectures were part of the university celebrating its twentieth anniversary in which prominent figures spoke about their field (Burnham, 2012). The purpose of this essay is to explore each of Freud’s lectures in detail in order to introduce psychoanalysis.

Before describing the lectures, it is important to understand how Freud mapped the mind. He divided it into three parts twice. The first time, he categorized it into the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious (Freud, 1938). The conscious layer contains everything that an individual is aware of, such as immediate physical experience. For example, a fresh cut, the first bite of a foreign dish, anything that attracts our attention. On the other hand, the preconscious contains what we are not aware of, but can bring forth to the conscious. This includes memories such as what an individual ate for lunch the day before. However, it is not limited to memories only, it also could also contain immediate physical experience that is not in the conscious such as background noise or proprioception. The last division is the unconscious. This encompasses elements that we are not aware of and are being repressed, which is an essential concept in psychoanalysis that will later be described. This material will not come forward to the conscious unless with the help of analysis.

Before describing the lectures, it is important to understand how Freud mapped the mind. He divided it into three parts twice. The first time, he categorized it into the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious (Freud, 1938). The conscious layer contains everything that an individual is aware of, such as immediate physical experience. For example, a fresh cut, the first bite of a foreign dish, anything that attracts our attention. On the other hand, the preconscious contains what we are not aware of, but can bring forth to the conscious. This includes memories such as what an individual ate for lunch the day before. However, it is not limited to memories only, it also could also contain immediate physical experience that is not in the conscious such as background noise or proprioception. The last division is the unconscious. This encompasses elements that we are not aware of and are being repressed, which is an essential concept in psychoanalysis that will later be described. This material will not come forward to the conscious unless with the help of analysis.

The second time he organized the mind, he divided it into the id, the ego, and the superego (Rana, 1997). The superego is the part of the mind that is the last to develop and is constantly reminding the ego of rules and morals; they could be social, political, religious, etc. The id, which is innate, is the most important component in psychoanalysis. It is constantly looking for pleasure. The next division is the ego. This plays the role of a moderator between the rules of the superego and the desires of the id. Moreover, the superego is both conscious and unconscious, as well as the ego. On the other hand, according to Freud, the Id is the only part of the strata that is solely unconscious. Nevertheless, according to the neuropsychoanalyst Mark Solms, there is a conscious id (Solms, 2013).

In the first lecture, Freud describes how hysteria was one of the foundations of psychoanalysis. He talks about one of his patients when he was working with Dr. Josef Breuer (Gray, n. d.). The patient was a twenty-year-old woman who was experiencing physical symptoms such paralysis, loss of sensation, trouble with her vision and speech, and for several weeks she experienced hydrophobia. Another symptom was a condition called absence, where she seemed to disconnect from reality and concentrated on a special thought. When she was in this condition, she usually muttered certain words. Dr. Breuer wrote down the words and tried to use them as a starting point in order to induce hypnosis. When the patient was hypnotized, she could talk about what she was thinking during her absences, which were usually fantasies or memories. After she explored her fantasies while being under hypnosis, the physical symptoms of hysteria disappeared. She called this method of treatment the talking cure. Her picture can be found on the right side of this paragraph.

In the first lecture, Freud describes how hysteria was one of the foundations of psychoanalysis. He talks about one of his patients when he was working with Dr. Josef Breuer (Gray, n. d.). The patient was a twenty-year-old woman who was experiencing physical symptoms such paralysis, loss of sensation, trouble with her vision and speech, and for several weeks she experienced hydrophobia. Another symptom was a condition called absence, where she seemed to disconnect from reality and concentrated on a special thought. When she was in this condition, she usually muttered certain words. Dr. Breuer wrote down the words and tried to use them as a starting point in order to induce hypnosis. When the patient was hypnotized, she could talk about what she was thinking during her absences, which were usually fantasies or memories. After she explored her fantasies while being under hypnosis, the physical symptoms of hysteria disappeared. She called this method of treatment the talking cure. Her picture can be found on the right side of this paragraph.

An example of how one of her trains of thought connected to her symptoms is in the following story. During one summer, the patient visited a friend who kept a dog as their pet. This dog would drink from the glass of water of her friend, and her friend would later drink from it too. The patient explained that she had a negative opinion of her friend (she never used the word friend, but rather lady-companion), but this event was what disgusted her the most. When the patient finished telling this story, she was able to drink water once again, which meant that her symptom of hydrophobia had disappeared.

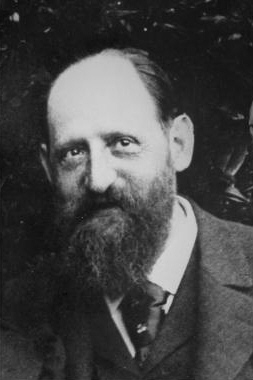

This connection between memories and physical symptoms was present in every hysteric patient. He concluded from this that “hysterical patients suffer from reminiscences” (Freud, 1909). In other words, the symptoms are expressions of memories. The next thing to explore is what kind of memories create the basis for hysteria. For Freud, it was events that caused suppression or repression, the former consists of making a conscious effort to remove a thought or feeling from consciousness, while the latter is its unconscious counterpart. An example of repression is seen in the hydrophobic patient who repressed her feelings of disgust. Moreover, another notion that Freud found important is the evidence of conscious and unconscious states of the patient. When Freud's patient was absent, she was able to recall the memories that were later traced back to her symptoms. On the other hand, when she was not absent, the patient was not aware the memories existed. Thus, Freud asserted that the wish contained in these expressions and in the memories was unconscious and it was brought to the conscious thanks to this new form of treatment. Therefore, the psychoanalytic method could be used to relieve the patient of its hysteria. A photograph of Dr. Breuer can be found to the left.

This connection between memories and physical symptoms was present in every hysteric patient. He concluded from this that “hysterical patients suffer from reminiscences” (Freud, 1909). In other words, the symptoms are expressions of memories. The next thing to explore is what kind of memories create the basis for hysteria. For Freud, it was events that caused suppression or repression, the former consists of making a conscious effort to remove a thought or feeling from consciousness, while the latter is its unconscious counterpart. An example of repression is seen in the hydrophobic patient who repressed her feelings of disgust. Moreover, another notion that Freud found important is the evidence of conscious and unconscious states of the patient. When Freud's patient was absent, she was able to recall the memories that were later traced back to her symptoms. On the other hand, when she was not absent, the patient was not aware the memories existed. Thus, Freud asserted that the wish contained in these expressions and in the memories was unconscious and it was brought to the conscious thanks to this new form of treatment. Therefore, the psychoanalytic method could be used to relieve the patient of its hysteria. A photograph of Dr. Breuer can be found to the left.

In the second lecture, Freud explained he discarded hypnosis, which was a central component in the process of relieving hysterical symptoms, because not all of the patients could undergo a hypnotic state. Keeping in mind that the catharsis was what aided hysteric patients, Freud tried to replicate this with individuals in their normal state. He based this direction on a demonstration by Bernheim in 1889. This French neurologist showed that people who had been put into a hypnotic state of somnambulism reported, once awake, to not remember what had occurred when they were hypnotized. Nevertheless, when Bernheim insisted that they did, the events became conscious. Freud drew a parallel between these two events, the demonstration of Bernheim and his own practice, by noting that repressed memories could be recovered if individuals were pressed for information. Therefore, Freud used suggestion as technique for people in normal state to relieve them of their symptoms. Thus, when a patient reported that they did not remember something, Freud said that the memory would become accessible the instant when he touched their foreheads. He quickly abandoned this because he asserted that it was exhausting and consumed a lot of time.

It is important to explain that he was careful in not utilizing leading questions or influencing his patients' answers when using this technique. Thanks to these findings, he started to develop a theory that explained the etiology of hysteria. Freud argued that there was a force, which he named resistance, that prevented the expression of desires and thus created this pathological condition. He explained that one process of resistance was repression. The cause of repression was a result of the dynamics of the mind. He describes this process by saying that the Id contained a drive towards pleasure. Nevertheless, because it is incompatible with the rules of the superego, the ego represses it into the unconscious. Thus, a wish can be fulfilled without breaking the subject’s ethical standards.

Another example of the dynamics of the mind can be seen by another patient of Freud. This female patient felt attracted to the husband of his sister. When the patient’s sister died, she constantly thought "now he can marry me." Her wish was to be with her brother-in-law. Nevertheless, that thought became repressed by the ego because the superego's standards create a conflict with the statement. When the patient was in Freud’s practice, she reported that she did not remember this event, but after she told him this story (the memory was no longer repressed) her hysterical symptoms disappeared.

An important characteristic of Freud’s model of the mind is that each component is not independent of the other, every part is in constant interaction with each other and that our behaviors, thoughts, feelings, etc., are the outcome of the struggle between these entities. Another important feature is the notion that even though a wish has been repressed or suppressed, it has by no means disappeared. It now exists in the unconscious where it is still trying to be fulfilled. By talking about it in a psychoanalytic setting, it becomes conscious without breaking the rules of the superego. To summarize the first two chapters, memories and fantasies are connected to hysteric symptoms and the dynamic between the parts of the mind are responsible for repressing or expressing desires.

In the third lecture, Freud kept discussing the topic of repression. He explained that when he suggested to patients that they did remember a memory that was linked to their hysterical symptoms, the patients talked about memories or ideas, that were not related, at least in an obvious way, to their symptoms. Nevertheless, he thought that these sets of ideas were still connected to the source of hysteria, but the connection was not explicit because the ideas were being repressed. Freud made the remark that his colleague, Dr. Carl Jung, later supported this concept with research. In other words, ideas or thoughts are connected by means of associations and the more resistance presented by the subject, the more the first set of thoughts would be distorted.

It has already been stated that hysterical symptoms were a form of expression of what an unfulfilled wish. The memories recalled by patients were also a form of an expression of said wish since they were associated to the true event that caused the repression or the suppression. The conscious substitutes of repressed thoughts are not only seen in patients with hysteria, but also in the everyday life. Freud described several types of ways where this process can be seen. One of them is by telling jokes. In his third lecture, Freud told the following joke: “Two not particularly scrupulous business men had succeeded, by dint of a series of highly risky enterprises, in amassing a large fortune, and they were now making efforts to push their way into good society. One method, which struck them as a likely one, was to have their portraits painted by the most celebrated and highly-paid artist in the city, whose pictures had an immense reputation. The precious canvases were shown for the first time at a large evening party, and the two hosts themselves led the most influential connoisseur and art critic up to the wall on which the portraits were hanging side by side. He studied the works for a long time, and then, shaking his head, as though there was something he had missed, pointed to the gap between the pictures and asked quietly: ‘But where’s our saviour?”’ (Freud, 1905a). Freud explained that the connoisseur’s Id contained a wish to express to the businessmen that they were thieves. However, directly stating this is not appropriate,which is why resistance enabled repression. However, instead of the thought being expressed as a symptom of hysteria, the mind found that it could articulate the same notion by means of a joke. This means that jokes allow repressed material to come forward without conflicting with the superego’s standards. In other words, the connoisseur was able to insult the businessmen without offending them.

The lectures have shown thus far that everyday activities such as telling jokes, verbalizing memories, and free associating can be analyzed to understand what is repressed into the unconscious. Moreover, this analysis can remove hysterical symptoms by bringing repressed items into the conscious. Additionally, Freud explained that repression, suppression, and resistance could be the result from the different strata and components of the mind interacting with each other. One of the other outcomes that Freud explains is the inability to free associate. An example of this are thoughts that are difficult to distort or the ones can be traced back easily to their source of origin. This is why, Freud argues, sometimes subjects report that they cannot continue talking during the psychoanalytic session.

Another method in which psychoanalysts explore the unconscious, besides free association, is by dream interpretation. The relevance of this technique can be seen when Freud states that “dreams are the royal road to the unconscious” (Freud, 1900). He discussed how the dreams of adults may seem like random nonsense. Nevertheless, children's dreams display clearly that they are wish-fulfillments that were not satisfied the day before. Additionally, he asserted that adults' dreams are also wish-fulfillments, but their content is distorted. In other words, dreams are the disguised wish-fulfillment of repressed wishes.

In addition, Freud divided the content of dreams into manifest and latent content. The former is what is explicitly in the dream such as imagery, conscious thoughts, etc. Moreover, the physical representations present in the dream are from events that occurred the day before. On the other hand, latent content are the unconscious ideas represented by the manifest content. He continues his lecture by stating that the events that occurred during the day become repressed. However, when individuals fall asleep, the mechanism that restrains thoughts from entering the conscious is weakened; resistance is no longer effective. Similarly to before, patients free associated, this time to the manifest content, in order to understand their repressed material. Additionally, there are two more outcomes that occur in dreaming that result from the ego, superego, and id's interaction, which are condensation and displacement. Evidence of the former can be seen in how the manifest content can represent several latent elements (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2016a). Displacement is when a wish that can be fulfilled one way is redirected in order to be fulfilled in another (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2016b). For example, if a desire to urinate is ultimately unfulfilled when an individual is awake, a person can dream that he or she is peeing. Therefore, individuals can still fulfill wishes by dreaming; even though, the wish is not fulfilled in real life.

In addition, Freud divided the content of dreams into manifest and latent content. The former is what is explicitly in the dream such as imagery, conscious thoughts, etc. Moreover, the physical representations present in the dream are from events that occurred the day before. On the other hand, latent content are the unconscious ideas represented by the manifest content. He continues his lecture by stating that the events that occurred during the day become repressed. However, when individuals fall asleep, the mechanism that restrains thoughts from entering the conscious is weakened; resistance is no longer effective. Similarly to before, patients free associated, this time to the manifest content, in order to understand their repressed material. Additionally, there are two more outcomes that occur in dreaming that result from the ego, superego, and id's interaction, which are condensation and displacement. Evidence of the former can be seen in how the manifest content can represent several latent elements (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2016a). Displacement is when a wish that can be fulfilled one way is redirected in order to be fulfilled in another (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2016b). For example, if a desire to urinate is ultimately unfulfilled when an individual is awake, a person can dream that he or she is peeing. Therefore, individuals can still fulfill wishes by dreaming; even though, the wish is not fulfilled in real life.

In the last part of his third lecture, Freud discussed the topics explored in his book “Psychopathology of Everyday Life.” As stated before, he asserted that concepts like repression and resistance were not limited to hysteric patients only, but that they occur to everyone everyday. Other defense mechanisms include the inability to recall something even when it is known, the slips of the tongue (now known as Freudian slips), as well as reading or writing in an accurate manner (Freud, 1904). These mechanisms serve the same purpose of satiating an unconscious desire.

In his fourth lecture, Freud talked about the discoveries made using the techniques mentioned above. Mainly, that sexuality was an important factor that was being repressed in both children and adults. This caused Freud to report that sexual drives were innate and universal, which created controversy since at the time it was believed that the development of sexuality was non-present during childhood (Freud, 1905b). In addition, Freud too, at first, doubted that his assertion was correct. He thought that the patients he analyzed with Breuer were the only ones that experienced an abnormal sexual, which in turn formed part in the etiology of their hysteria. However, as time passed, he observed a pattern in all of the people he analyzed whether they had hysteria or not.

He named this pattern of sexual development in childhood Oedipus complex (Lapsley, 2011). This refers to how male children are at first in love with their mothers because they are the providers of pleasure, such as food, warmth, etc. The complex also involves feelings of jealousy towards the father since he is the the object of love for the mother. This is obviously repressed. However, to support his theory of infantile sexuality, Freud shared a paper of a faculty member of Clark University. The name of the paper was “A Preliminary Study of the Emotion of Love between the Sexes,” and it stated that the appearance of what the author called “sex-love” did not make its initial original appearance in individuals who were in their teenage years, but rather when they were just children.

He named this pattern of sexual development in childhood Oedipus complex (Lapsley, 2011). This refers to how male children are at first in love with their mothers because they are the providers of pleasure, such as food, warmth, etc. The complex also involves feelings of jealousy towards the father since he is the the object of love for the mother. This is obviously repressed. However, to support his theory of infantile sexuality, Freud shared a paper of a faculty member of Clark University. The name of the paper was “A Preliminary Study of the Emotion of Love between the Sexes,” and it stated that the appearance of what the author called “sex-love” did not make its initial original appearance in individuals who were in their teenage years, but rather when they were just children.

In his fifth lecture, Freud talked about transference, which is another way wishes can be fulfilled. This is when an emotion that is felt towards a specific person is redirected towards another, usually the psychoanalyst (Felluga, n. d.). This allows the repressed erotic and aggressive wishes to be satisfied while complying with the superego. Freud argued that this was the implicit way human beings engaged in a therapeutic procedure in order to relieve tension caused by the dynamics between the Id and Superego. Finally, Freud argues that there are three possible outcomes that occur after the repressed material becomes conscious. The first one is that the individual replaces their repression with a condemning judgment about their unconscious material. The second result is that after an individual understands his or her own drives the subject can engage in a behavior that is similar to the defense mechanism known as sublimation. This refers to finding socially accepted activities that permit the person to indulge in his or her desires without breaking moral standards. An example of this is becoming aware of the drive that motivates someone to engage in aggressive behavior, then redirecting this into a more socially appropriate activity such as mixed martial arts. If this action takes place, then the individual is allowed to be aggressive without breaking a social rule. The third possible result is the replacement of a hysterical symptom to a new one.

In conclusion, Freud stated that there was a constant interaction between the id, the ego, and the superego. The outcomes produced by the dynamics of the mind are usually unconscious and aid in relieving tension. These mental products include dreams, transference, slips of the tongue, forgetting, mispronouncing, misplacing, and hysterical symptoms. Nevertheless, the latter can be removed and the rest understood through psychoanalytic therapy.

References

Burnham, J. C. (2012). After Freud left: A century of psychoanalysis in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Felluga, Dino. (n. d.). "Modules on Freud: Transference and Trauma ." Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. Purdue U. Retrieved April 27, 2016, from <http://www.purdue.edu/guidetotheory/psychoanalysis/freud5.html>.

Freud, S. (1938). An Outline of Psychoanalysis. New York: W.W. Norton.

Freud, S. (1909). Five lectures on psychoanalysis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Freud, S. (1905a). Jokes and their relation to the unconscious.

Freud, S. (1900). The Interpretation of Dreams.

Freud, S. (1904). The Psychopathology of Everyday life. New York: Norton.

Freud, S. (1905b). Three contributions to the theory of sex. New York: Dutton.

Gray, R. (n.d.). Freud, "Aetiology of Hysteria" Retrieved April 27, 2016, from http://courses.washington.edu/freudlit/Hysteria.Notes.html

Jay, M. E. (2016). Sigmund Freud. Retrieved April 27, 2016, from http://www.britannica.com/biography/Sigmund-Freud

Lapsley, D. K. (2011). Id, Ego, and Superego. Retrieved April 27, 2016, from http://www3.nd.edu/~dlapsle1/Lab/Articles & Chapters_files/Entry for Encyclopedia of Human Behavior(finalized4 Formatted).pdf

Rana, H. (1997). Sigmund Freud. Retrieved April 27, 2016, from http://www.muskingum.edu/~psych/psycweb/history/freud.htm

Solms, M. (2013). The Conscious Id. Neuropsychoanalysis, 15(1), 5-19. doi:10.1080/15294145.2013.10773711

Solms, M. (2013). The Conscious Id. Neuropsychoanalysis, 15(1), 5-19. doi:10.1080/15294145.2013.10773711

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. (2016). Condensation. Retrieved April 25, 2016, from http://www.britannica.com/topic/condensation-psychology

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. (2016). Displacement. Retrieved April 25, 2016, from http://www.britannica.com/topic/displacement-psychology

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. (2016). G. Stanley Hall. Retrieved April 25, 2016, from http://www.britannica.com/biography/G-Stanley-Hall

Comments

Post a Comment