"Do people use ten percent of their brain power?" Psychology Myths (Part 1 of 5)

Myth #1 People Use Only 10% of Their Brain Power

A long time ago, I learned about the myth that people only use 10% of the brain. At first, I thought that only individuals who were not in the field of psychology or neurology would believe this misconception. However, this changed when I read a study that found that one-third of psychology students believed that people only use one-tenth of their brain power (Higbee & Clay, 1998, p. 471). Then, when people kept asking me what I thought about humans only being capable of using ten percent of their brain and reading similar articles like one that found that 59% of a sample of individuals who went to college in Brazil believe the ten percent myth and that six percent of neuroscientists agreed (Herculano-Houzel, 2002), I understood that I was reading about one of the most prevalent myths in psychology.

(If you would like to learn more about this and other myths check out 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology by clicking this link)

(If you would like to learn more about this and other myths check out 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology by clicking this link)

History

Where did it come from? Well, it's difficult to pinpoint its origin, but it seems that it originated when William James wrote that he doubted that people used more than 10% of their intellectual capacity. Then, some people slowly transformed that statement into one that made the claim it was 10% of the brain. Moreover, the journalist Lowell Thomas stated that it came from William James. He wrote this in the preface of "How to Win Friend and Influence People," which has sold 15 million copies worldwide. Others believe that Albert Einstein used this claim in order to explain his intelligence, but the staff at Albert Einstein did not find evidence of this.

Why is it so prevalent?

There are several reasons this myth has not died. First of all, it would be good news to know that we have room to improve our memory, intelligence, etc. and a vast amount of people take an advantage of this to sell hope. For example, Robert K. Cooper wrote a book called "The Other 90%: How to unlock your vast untapped potential for leadership and life."

Other books where the ten percent claim is present includes "How to Be Twice as Smart," by Scott Witt. He wrote on page four that "If you are like most people you're using only ten percent of your brain power."

In addition, it has been used over and over in the big and small screen. A good example would be the movie "Lucy." Spoiler alert! The plot revolves around a woman who slowly gains access to more parts of her brain thanks to a drug. She starts by being able to speak other languages, but, by the end of the movie she has superpowers.

Do we use our whole brains, but only 10% at a time?

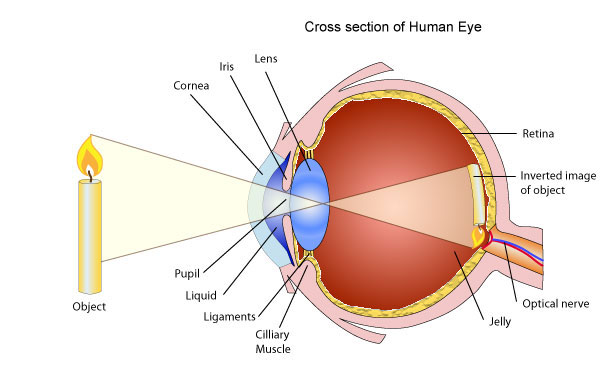

Not long after I published this post, I received the question: "What if we use ten percent, but only at a given task?" In other words, if we ignore the brain parts in charge of vital functions such as breathing, do individuals use ten percent of the brain for a specific task such as vision? Well, the answer would still be the same, we don't ignore 90% of the brain while doing a specific activity. If we continue with the example of vision, this becomes evident. Vision starts in the eyes.

In here, there is a part known as the retina, which contains cells that transduce light into electrical signals in the brain. The eye is connected to the optic nerve, which is one of the twelve cranial nerves. Moreover, the information goes through here until it reaches the optic chiasm where it crosses to the other side of the hemisphere. Then, the lateral geniculate nucleus receives input from the optic tract and sends it into the occipital lobe.

From the striate cortex, the information is distributed to different pathway in order to be analyzed what the visual information actually is and where it is. As it now becomes evident, a large portion of the brain is used in a simple activity such as looking directly at an object. In addition, more pathways are used with more complex behaviors. For example, by looking at an incoming car and stopping from walking across the street, individuals are utilizing their prefrontal cortex and their motor cortex.

Have we reached our limits?

According to Dr. Gordon, a behavioral neurologist and cognitive neuroscientist, who had an interview published in Scientific American in 2008, we use virtually every part of the brain. Does this mean that people have reached their limits? Well, no. Research explains that the best way to improve is not by unlocking secret areas of the brain, but rather by being diligent (Beyerstein, 1999; Druckman & Swets, 1988). Nevertheless, people still believe that there is a possibility that they will unlock that 90%. In fact, this finding has not changed the convictions of believers of the myth (Beyerstein, 1999). But, can we change that?

Feel free to leave a comment, questions, concerns, or suggestions.

Beyerstein, B. L. (1999). Whence cometh the myth that we only use ten per cent of our brains? In S. Della Sala (Ed.), Mind myths: Exploring popular assumptions about the mind and brain (pp. 1–24). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Carnegie, D. (1981). How to win friends and influence people (Rev. ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster.

Druckman, D., & Swets, J. A. (1988). Enhancing human performance: Issues, theories, and techniques. Washington, DC, US: National Academy Press.

Herculano-Houzel, S. (2002). Do you know your brain? A survey on public neuroscience literacy at the closing of the decade of the brain. Neuro- scientist, 8(2), 98–110.

Higbee, K. L., & Clay, S. L. (1998). College students' beliefs in the ten-percent myth. The Journal Of Psychology: Interdisciplinary And Applied, 132(5), 469-476. doi:10.1080/00223989809599280

Lilienfeld, S. (2010). 50 great myths of popular psychology: Shattering widespread misconceptions about human behavior. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

References

Beyerstein, B. L. (1999). Whence cometh the myth that we only use ten per cent of our brains? In S. Della Sala (Ed.), Mind myths: Exploring popular assumptions about the mind and brain (pp. 1–24). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Carnegie, D. (1981). How to win friends and influence people (Rev. ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster.

Druckman, D., & Swets, J. A. (1988). Enhancing human performance: Issues, theories, and techniques. Washington, DC, US: National Academy Press.

Herculano-Houzel, S. (2002). Do you know your brain? A survey on public neuroscience literacy at the closing of the decade of the brain. Neuro- scientist, 8(2), 98–110.

Higbee, K. L., & Clay, S. L. (1998). College students' beliefs in the ten-percent myth. The Journal Of Psychology: Interdisciplinary And Applied, 132(5), 469-476. doi:10.1080/00223989809599280

Lilienfeld, S. (2010). 50 great myths of popular psychology: Shattering widespread misconceptions about human behavior. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Comments

Post a Comment